Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health

Session: Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health 4

260 - Racial Disparities in Antibiotic Use for Hospitalized Children

Saturday, May 4, 2024

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM ET

Poster Number: 260

Publication Number: 260.1629

Publication Number: 260.1629

Jenna H. Tan (she/her/hers)

Medical Student

University of Washington School of Medicine

Seattle, Washington, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Racial disparities in antibiotic use have been demonstrated in pediatric outpatient settings but have not been assessed in pediatric inpatient settings. Respiratory infections are common in hospitalized children, where the choice to treat for potential bacterial superinfection is often determined by individual clinician decisions, which are susceptible to influence by unconscious bias and systemic racism.

Objective: We aimed to evaluate whether there were racial disparities in antibiotic prescribing for children admitted to our institution for treatment of respiratory infections.

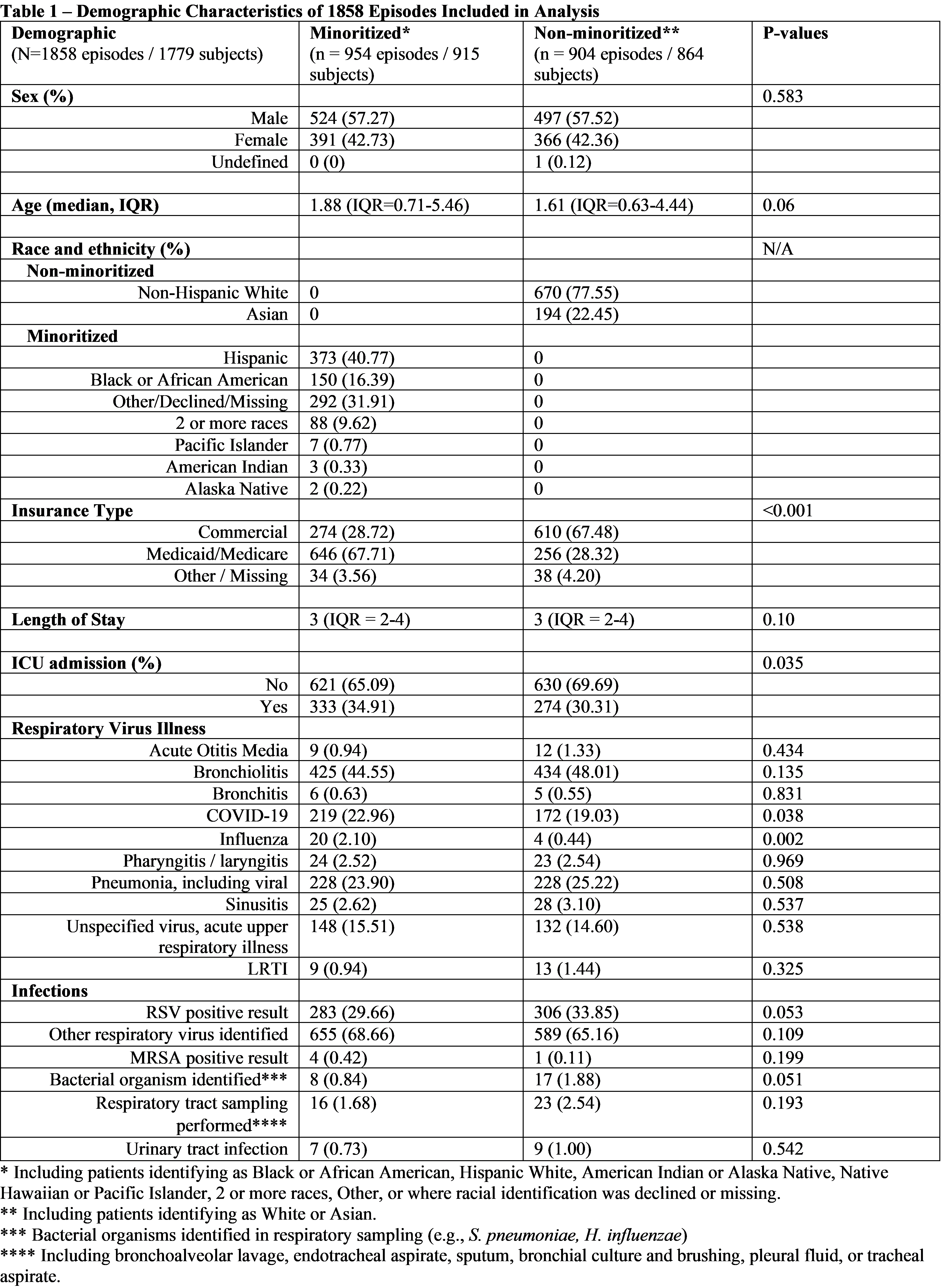

Design/Methods: This retrospective cohort study from October 2020 to April 2023 evaluated all patients with respiratory illnesses hospitalized at Seattle Children’s Hospital, identified using discharge diagnosis codes. Children with complex chronic conditions, length of stay greater than 7 days, hospital admission in the prior 30 days, and patients given medications for non-routine respiratory infections (e.g., tuberculosis) were excluded. We categorized subjects as being from minoritized or non-minoritized racial and ethnic groups, where we defined the minoritized group as children who self-identified as Black or African American, Hispanic, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 2 or more races, other race, or where self-identification was missing, because each of these groups are underrepresented among our medical staff, compared to our patient population. Differences in antibiotic use across the groups were analyzed via chi-squared tests. To account for potential confounders associated with broad-spectrum antibiotic use, we performed binomial regression with robust standard errors on the association between racial group and antibiotic receipt, adjusting for ICU admission and insurance type.

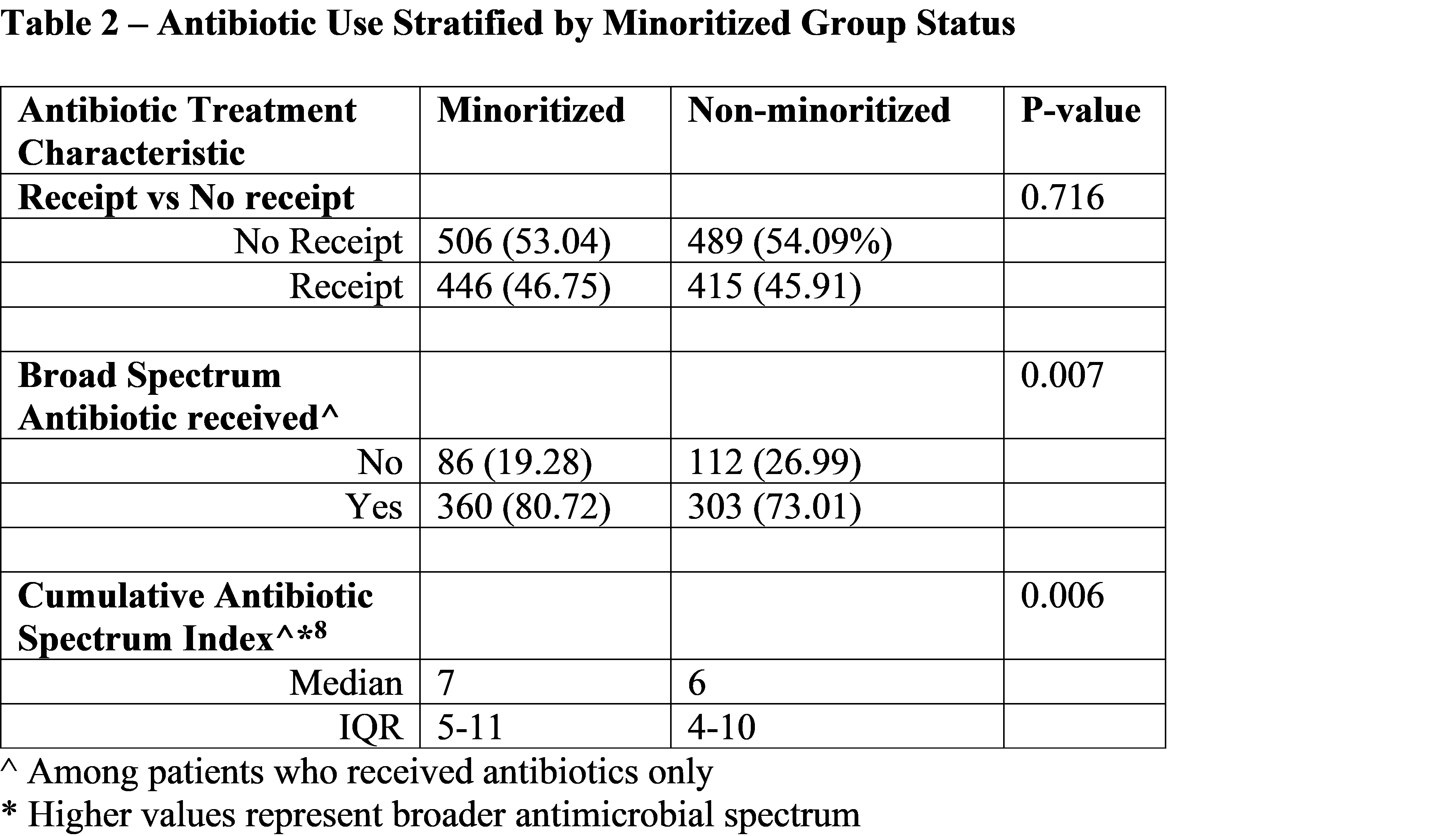

Results: Of 1,858 total encounters among 1,779 subjects, there was no statistically significant difference in antibiotic receipt between minoritized and non-minoritized children (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 1.08, 95% CI 0.97-1.20). However, minoritized children were more likely to receive broad-spectrum antibiotics than their counterparts (aRR 1.08, 95% CI 1.07-1.08).

Conclusion(s): In our institution, children from minoritized racial and ethnic groups hospitalized with respiratory infections were equally likely to receive antibiotics compared to their non-minoritized counterparts but were more likely to receive broad-spectrum antibiotics. Future research should seek to understand the factors driving this disparity and ways to ensure more equitable antibiotic use.