General Pediatrics

Session: General Pediatrics 4

358 - Cutting Through Confusion: Kids’ (Mis)understanding of Medical Terminology

Saturday, May 4, 2024

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM ET

Poster Number: 358

Publication Number: 358.1517

Publication Number: 358.1517

Michael B. Pitt, MD (he/him/his)

Professor of Pediatrics

University of Minnesota

Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Healthcare professionals often unintentionally use medical jargon. Improved understanding enables pediatric patients and their families to articulate their concerns, participate in decision-making, and self-advocate. Few studies have examined children’s understanding of medical terminology.

Objective: We sought to investigate what children understand from common medical phrases.

Design/Methods: We developed 11 prompts for phrases children may hear in a clinical setting and evaluated for internal validity prior to implementation. Children ages 4 to 12 years volunteered to participate in a survey at the 2023 Minnesota State Fair. Parents provided informed consent and demographic information, then children answered survey questions verbally with investigators recording responses. Subsequently, answers to each question were coded as correct, partially correct, or incorrect by two independent reviewers; a third reviewer settled any discrepancies. Logistic regression models were used to correlate age, gender, and exposure to medical care against correct answers.

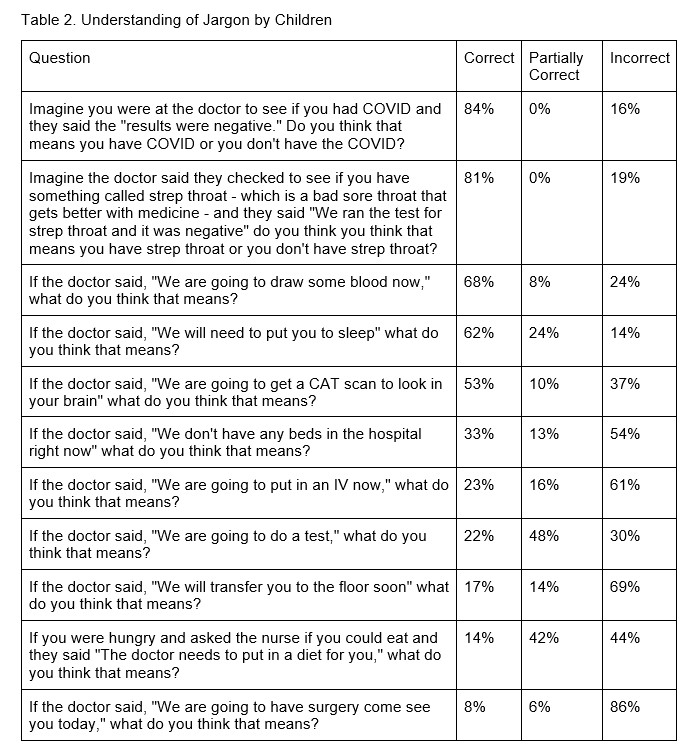

Results: 100 children completed the survey (Table 1) and showed a variable variable understanding of different medical phrases (Table 2). Most children understood the meaning of a negative test for COVID (84%) and strep throat (81%). 68% understood what it meant to have blood drawn, 62% understood the meaning of being put to sleep for a procedure, and 53% understood having a CT scan. One-third understood the meaning of no beds in the hospital, and 17% understood being transferred to the floor. Very few (8%) understood what it meant to have a surgical consultation, with many (56%) believing it meant they were to have an operation that day. Although most incorrect responses were benign (not knowing, confusing injection with IV, etc.), some were potentially frightening: thinking they would need to leave the hospital despite being sick, being asked to sleep on the floor without a bed, or being “put to sleep” like a euthanized animal. Older age was significantly associated with answering more questions correctly. Female gender had slight positive association, but personal or family exposure to healthcare had little effect.

Conclusion(s): Children’s understanding of medical terms varies, with older children more likely to understand medical terminology. Children as young as 4 years of age readily provided answers about their understanding of medical phrases, supporting the use of tools like teach-back in assessing children’s understanding of medical care plans.

.jpg)