Emergency Medicine

Session: Emergency Medicine 12: Potpourri

424 - Primary Care Access and Medical Home Prevalence Among Children Visiting a Canadian Pediatric Emergency Department

Monday, May 6, 2024

9:30 AM - 11:30 AM ET

Poster Number: 424

Publication Number: 424.2865

Publication Number: 424.2865

Jennifer Thull-Freedman, MD, MSc (she/her/hers)

Clinical Associate Professor

University of Calgary, Alberta Children's Hospital

Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Canadian emergency departments (EDs) are facing a crisis of overcrowding. Simultaneously, physician shortages and other health system challenges have left 1 in 5 Canadians without a primary care provider (PCP). Access barriers to primary care are associated with increased ED use. The Medical Home Model sets an international standard for quality in primary care.

Objective: To inform local quality improvement, we sought to determine the prevalence of features of a medical home among children visiting the ED of our urban tertiary children's hospital, to understand factors associated with lack of access to primary care, and reasons for presentation to our ED.

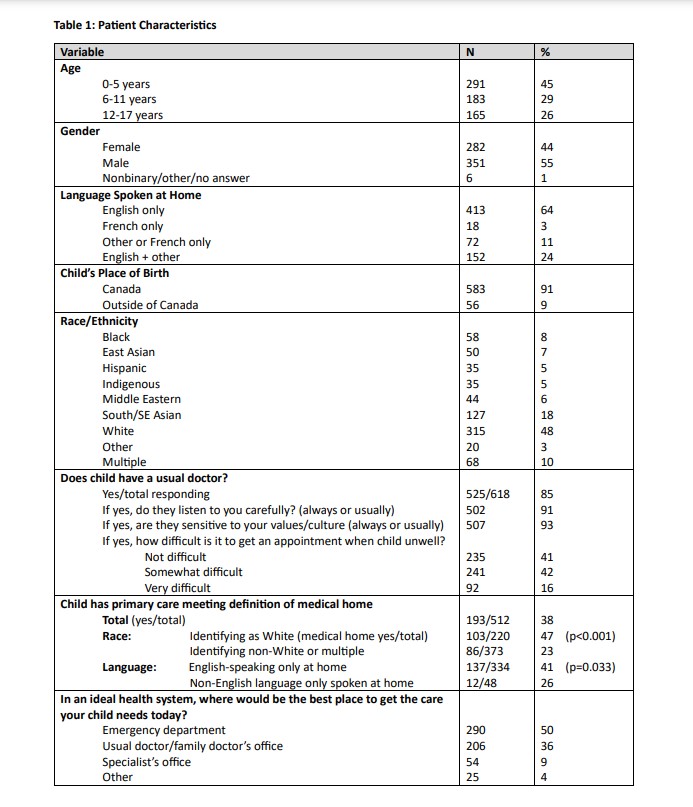

Design/Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional survey of parents or caregivers of patients age < 18 years visiting our ED. Participants were approached consecutively over seven 24-hour periods in September 2023. Patients were excluded if unstable, if residing out of province, or if they or a sibling already participated. Interpretation was offered. The primary outcome measure of the presence of a medical home was developed from the US Census Bureau National Survey of Child Health and adapted to local context. The medical home composite measure consisted of 5 subcomponents: having a usual doctor, a usual source of care, family-centred care, receiving needed referrals, and care coordination. Each domain required a positive response to be deemed to have a medical home. Outcomes were analyzed descriptively and with Chi-square analysis. Regression and geospatial analysis to further understand determinants of having a medical home are in progress. The project was exempted from research ethics review due to the primary purpose of quality improvement.

Results: Of 1477 patient visits during the enrollment week, 1290 were eligible. 64% were approached, and 78% of patients approached provided sufficient data for primary outcome analysis. Nine participants used interpretation. While 85% of respondents stated their child had a usual doctor, only 38% met the definition of having a medical home. The majority (58%) who reported having a usual doctor found it either somewhat or very difficult to get an appointment for an acute concern. Patients identifying as White (p < 0.00001) and those who speak only English at home (p=0.033) were more likely to have a medical home (Table 1).

Conclusion(s): Many patients visiting the ED experienced difficulty accessing primary care for acute concerns, and a significant proportion have primary care that does not meet the definition of a medical home. Race/ethnicity and language affected the likelihood of having a medical home.