Neonatology

Session: Neonatal Neurology 10: Neurodevelopment

353 - The Impact of Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury on Amygdala and Hippocampal Volume as Related to Anxiety

Monday, May 6, 2024

9:30 AM - 11:30 AM ET

Poster Number: 353

Publication Number: 353.2759

Publication Number: 353.2759

Amaryllis Fernandes, MD

Resident

Baylor College of Medicine

Houston, Texas, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Traumatic brain injury (TBI), one of the leading causes of childhood disability and death, is associated with a significantly increased risk for psychological health difficulties related in part to changes in structure and function of the amygdala and hippocampus.

Objective: Using a prospective longitudinal cohort design, we evaluated 1)the impact of childhood TBI on amygdala and hippocampal volumes across the first year post injury relative to healthy children (HC), and 2)group differences in the relation of these volumes with self-reported anxiety.

Design/Methods: Structural MRIs were obtained on children age 8-15 years who experienced TBI (n=51) and age matched HC (n = 36) at 7 weeks (Time1) and 14 months (Time2) post-injury. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) assessed self-reported anxiety at both timepoints. General linear models evaluated the relationship between SCARED and amygdala and hippocampal volumes, group, time, and their interactions. Pubertal status and sex were included as covariates.

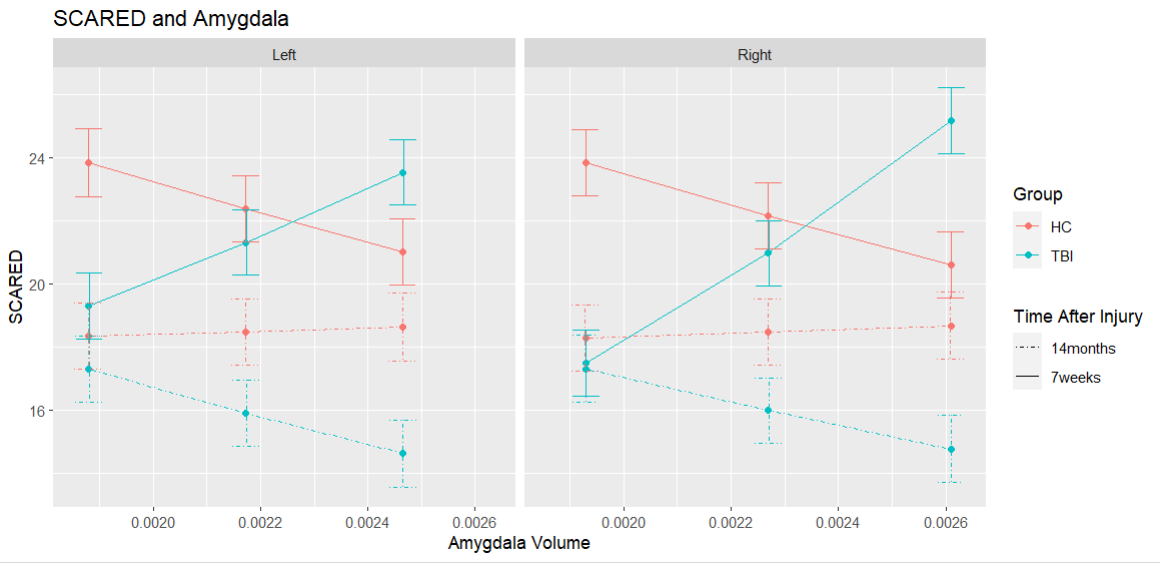

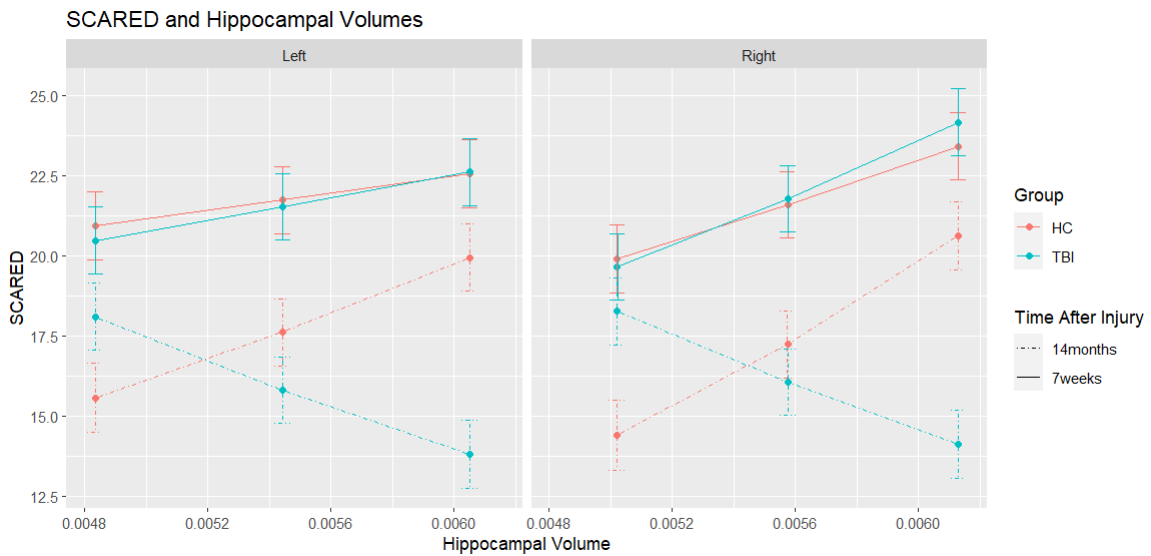

Results: Multivariable models revealed significant Group x Volume x Time interactions for bilateral amygdalae (p < 0.01) and hippocampi (p < 0.0001) on SCARED. In the amygdala, from Time1 to Time2 the HC’s relationship between volume and SCARED became less negative; in contrast the TBI group initially demonstrated a positive relationship between volume and SCARED which reversed at Time2. In the hippocampus, at both timepoints, the HCs showed a positive relationship between volume and SCARED, while the TBI group demonstrated a reversal of this pattern at Time2. Finally, there was a significant main effect of sex on SCARED for the bilateral amygdala and hippocampus: girls demonstrated higher SCARED than boys.

Conclusion(s): The amygdalae and hippocampi are stress-responsive structures associated with psychological health outcomes. Our findings indicate that pediatric TBI significantly impacted the relationship between volume of these structures and anxiety scores during the first year of recovery. For both structures, this relation was positive during the subacute stage and became negative by the chronic stage of recovery, with higher anxiety ratings associated with smaller volumes. The negative relation between amygdala volume and anxiety identified following TBI is similar to prior studies of youth experiencing psychological distress but differs from studies showing positive relations with parent ratings of child anxiety. TBI not only impacts the neuropsychiatric development of children, but these effects may be delayed over time.