Clinical Bioethics

Session: Clinical Bioethics

429 - Neonatologist Reactions to Uncertainty in Patient Care

Sunday, May 5, 2024

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM ET

Poster Number: 429

Publication Number: 429.1779

Publication Number: 429.1779

Erin Rholl, MD, MA (she/her/hers)

Assistant Professor, Neonatologist & Pediatric Palliative Care Physician

Medical College of Wisconsin

Medical College of Wisconsin

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: When providing care to critically ill infants, neonatologists and parents face situations of medical uncertainty. Uncertainty can arise around: 1) the patient’s diagnosis and cause of illness, 2) the prognosis, including potential mortality or morbidities, 3) the best steps to evaluate or treat a condition, 4) what interventions to offer, and 5) where to set limits on medical interventions when prognosis is poor. Little is known about how neonatologists experience and manage uncertainty in practice.

Objective: Describe neonatologist reactions to types of uncertainty in patient care.

Design/Methods: This study utilized the validated revised Physicians’ Reactions to Uncertainty Scale. We added questions to further describe situations of uncertainty experienced in neonatology focusing on the 5 types listed above. The additional questions were refined utilizing cognitive interviews. We anonymously surveyed neonatologists using the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine listserv. We utilized descriptive statistics, Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test and linear-by-linear association tests as appropriate.

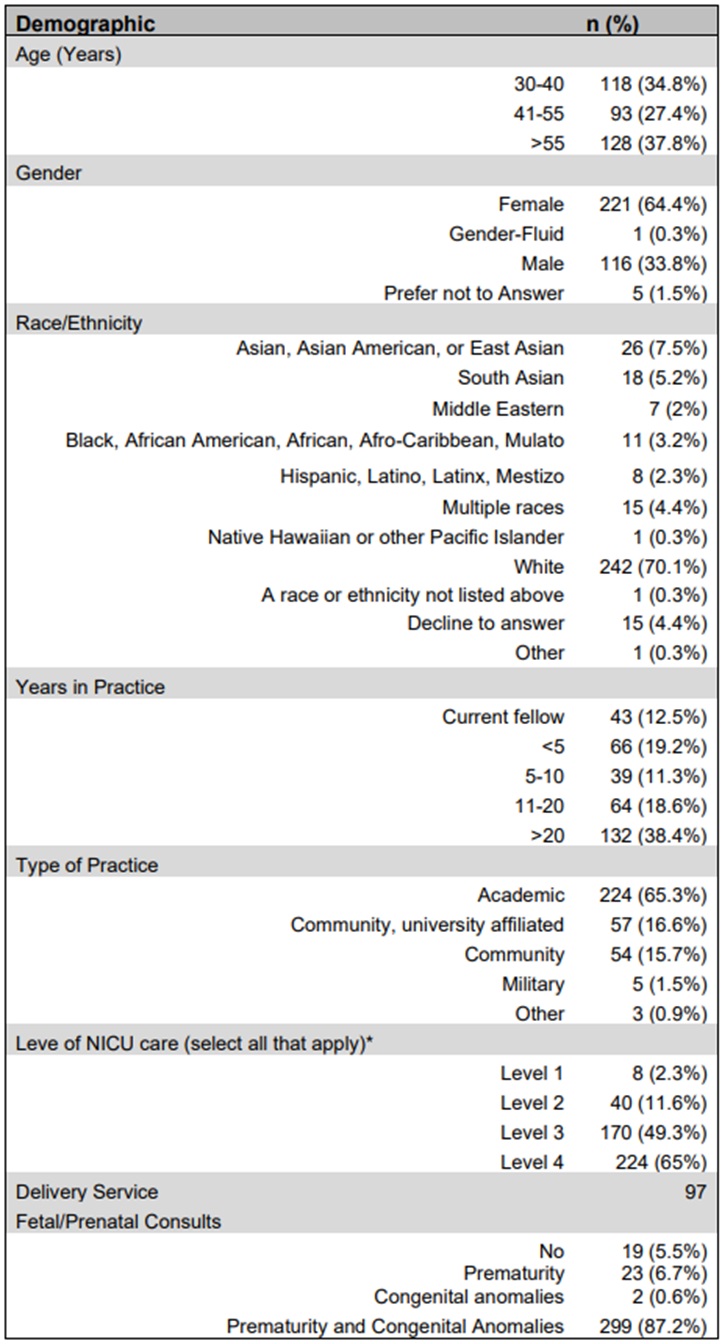

Results: 345 neonatologists completed the survey. Respondents were from all AAP districts, predominantly female (64%) and practiced at academic (65%) level IV (65%) units (Table 1). In general, neonatologists expressed a range of discomfort for all 5 types of uncertainty. For all types, there was an association between years in practice and comfort with uncertainty (P < 0.001) except for a slight increase in discomfort from < 5 years in practice to 5-10 years in practice. Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate this for diagnostic uncertainty and limit setting. Overall, comfort with uncertainty did not differ by respondents reported gender with several exceptions. More female than male respondents slightly to strongly agreed that they feared being held accountable for the limits of their knowledge (P = 0.033) and worried about losing trust with the family if their recommendation was grounded in inaccurate prognostication (P = 0.0052). Nearly all respondents agreed that uncertainty should be shared with families (94%) and disclosure improves their relationship with families (96%). Similarly, the vast majority of respondents reported discussing cases with high degrees of prognostic uncertainty with their colleagues (95%) and where to set limits in those cases (94%).

Conclusion(s): Neonatologists report a range of comfort levels with different types of uncertainty faced in patient care. Strategies to support neonatologists in communicating with families around uncertainty are needed.

.jpg)

.jpg)