Children with Chronic Conditions

Session: Children with Chronic Conditions 1

259 - Differences in COVID-19 Testing Perceptions from Caregivers of Children with Medical Complexity by Rurality Status

Friday, May 3, 2024

5:15 PM - 7:15 PM ET

Poster Number: 259

Publication Number: 259.132

Publication Number: 259.132

Kristina Devi Singh-Verdeflor, MPH (she/her/hers)

Research I

University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health

Madison, Wisconsin, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Rural children experience stark disparities in healthcare access and quality. The intersection of rurality and medical complexity is a crucial but under-researched domain. Since children with medical complexity (CMC) have worse COVID-19 outcomes, understanding rural-urban differences in COVID-19 testing perceptions might guide ongoing efforts to manage viral transmission.

Objective: To investigate associations between rurality and testing perceptions for caregivers of CMC.

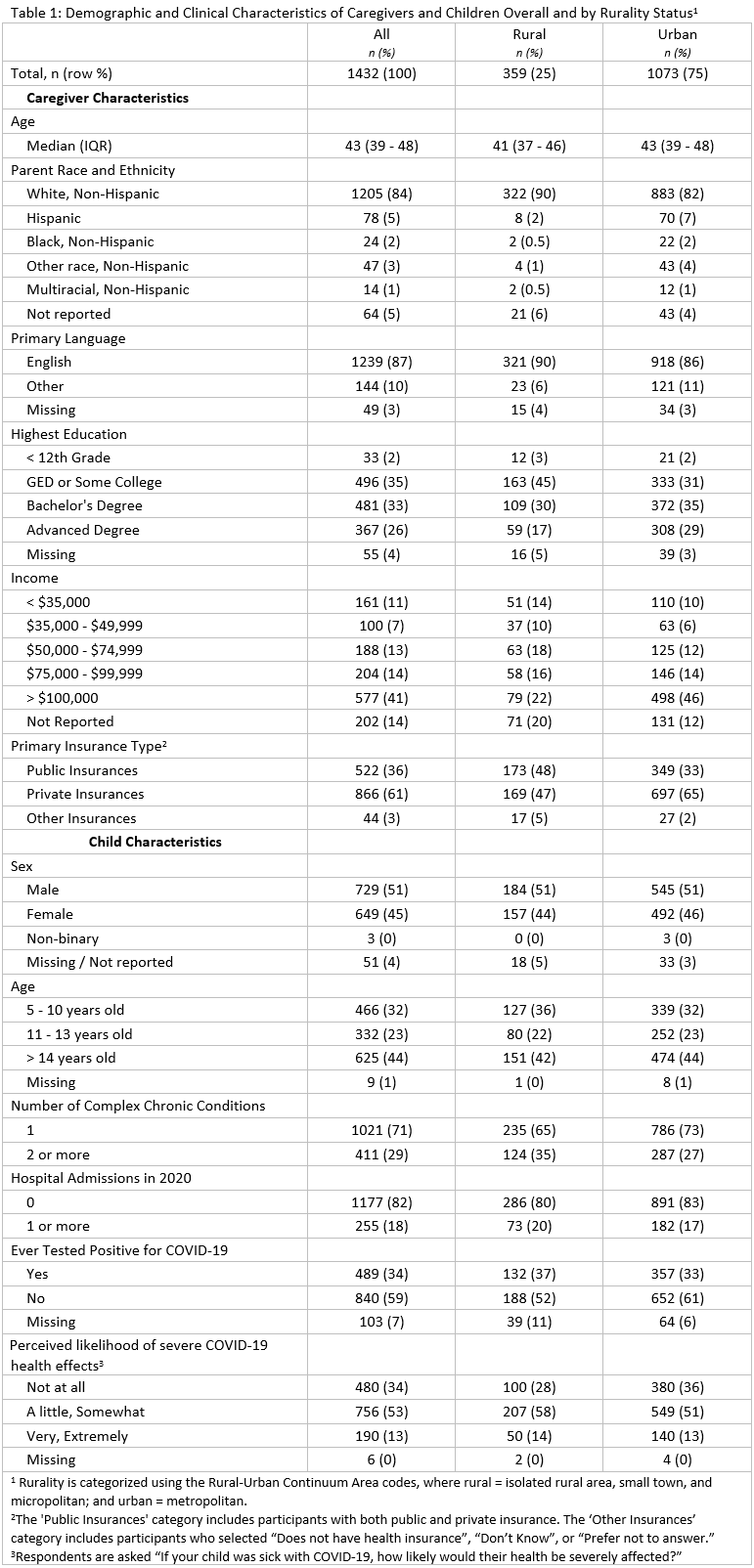

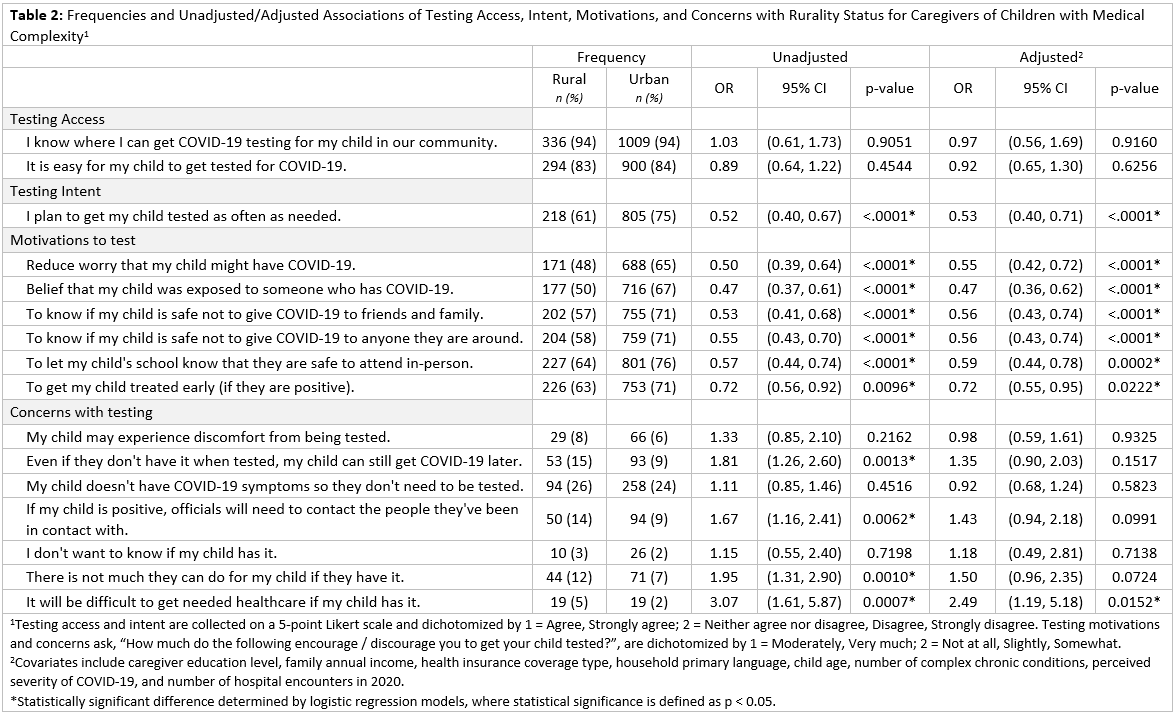

Design/Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional survey (April – June 2022) of English- and Spanish- speaking primary caregivers of children with at least 1 complex chronic condition (CCC) between ages 5-17 years, at an academic medical center in the Midwest. Survey content was derived from the NIH’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics-Underserved Populations Common Data Elements Library. Rurality was dichotomized using the Rural-Urban Continuum Area codes (Isolated Rural Area / Small town / Micropolitan vs. Metropolitan). Outcomes represented COVID-19 testing access, intent, motivators, and concerns. Covariates included caregiver education level, annual income, health insurance type, primary language, child age, number of CCCs, perceived severity of COVID-19, and number of hospital encounters in 2020. Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses examined associations between rurality and each outcome.

Results: Among 1432 responses, (response rate = 49%), 359 (25%) were classified as rural. Respondents had varied education, income, and insurance levels, with 35% of rural and 27% of urban children reporting ≥ 2 CCCs (Table 1). In the multivariable models (Table 2), rural and urban caregivers reported similar testing access, but rural caregivers had significantly less testing intent (aOR [95% CI]: 0.53, [0.40, 0.71]). Further, the motivators to test (e.g., reduce worry, prevent transmission, access care earlier), were significantly less important to rural caregivers (0.55 [0.42, 0.72], 0.56 [0.43, 0.74], 0.72 [0.55, 0.95], respectively). Notably, the prominent concern with testing for rural caregivers was “It will be difficult to get needed healthcare if my child has it” (2.49 [1.19, 5.18]).

Conclusion(s): Despite comparable testing access and greater medical complexity, our study revealed substantial disparities in testing intent, motivation, and concern among rural caregivers. Understanding the reasons for these differences and whether they extend to other transmissible illnesses such as influenza are important for effective public health messaging and ensuring more equitable health outcomes.