Hospital Medicine

Session: Hospital Medicine 5

146 - Can Antibiotics Prevent Progression to Complicated Pneumonia in Children?

Saturday, May 4, 2024

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM ET

Poster Number: 146

Publication Number: 146.1297

Publication Number: 146.1297

- MB

Mark Brittan, MD, MPH

Associate Professor

University of Colorado

Aurora, Colorado, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: : It is unknown whether antibiotics started after the initial diagnosis of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) prevents progression to complicated pneumonia.

Objective: To evaluate if antibiotics given after the diagnosis of an LRTI in the emergency department (ED) or outpatient (OP) setting is associated with a subsequent diagnosis of complicated pneumonia.

Design/Methods: A case control study was conducted using the 2009-2019 Colorado All Payer Claims Data selected for children 0-18 years old with at least one LRTI diagnosis. Cases were defined as those with a diagnosis of complicated pneumonia within 2-14 days following the child’s initial LRTI based on ICD-9/10 diagnostic and procedure codes for pleural effusion, empyema, thoracostomy, thoracostomy tube, thoracoscopic drainage, and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Controls (i.e., those with LRTI but no subsequent complicated pneumonia) were matched (3:1 ratio) based on age, insurance status, setting (ED or OP), and month and year of initial LRTI. The exposure was an oral antibiotic prescription fill occurring two days before to 14 days after the initial LRTI encounter, and prior to the complicated pneumonia diagnosis (for cases). Covariates included presence of a complex chronic condition (CCC), location (ED vs. OP), LRTI type (viral vs. bacterial/indeterminate), and history of PCV or HiB vaccine. Conditional logistic regression was used to assess the association between antibiotic exposure and complicated pneumonia while controlling for covariates.

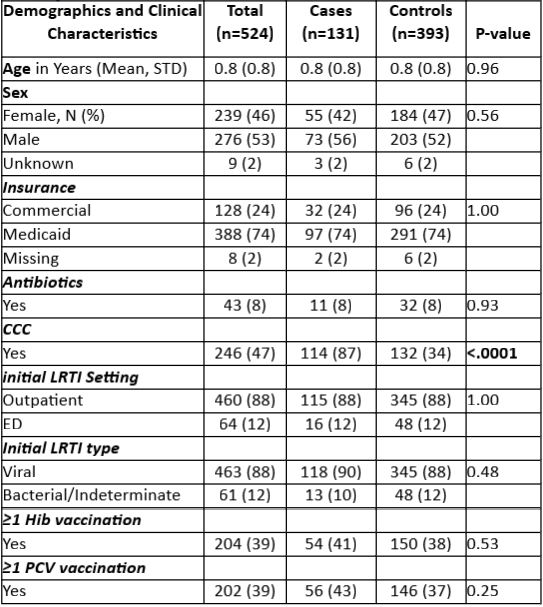

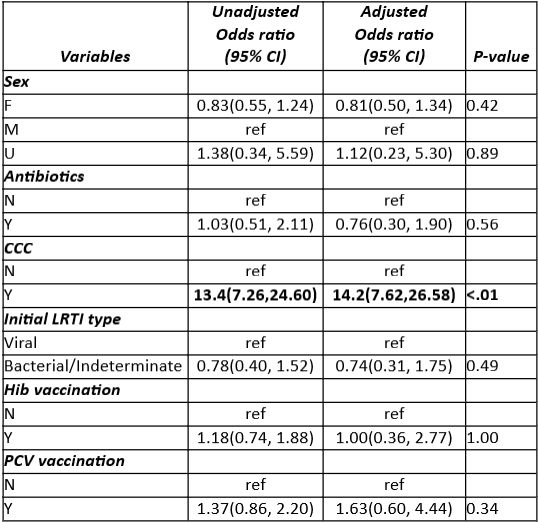

Results: We identified 131 cases matched to 393 control patients, with a mean age of 0.8 years. In bivariate analysis, there were no differences in demographic or clinical characteristics between groups except for presence of a CCC which heavily favored cases (87% vs. 34%; p<.001; Table 1). Antibiotic exposure was equivalent between cases (8%) and controls (8%). In conditional logistic regression analysis, there was no association between receiving antibiotics following initial LRTI and subsequent development of complicated pneumonia (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] 0.76; 95% CI 0.3, 1.9; p=0.56). Of the remaining covariates, only presence of a CCC was associated with the outcome (AOR 14.2; 95% CI 7.6,26.6; p<.01; Table 2).

Conclusion(s): Antibiotics given after an uncomplicated LRTI diagnosis do not appear to prevent progression to complicated pneumonia. As most LRTIs in young children are viral, this represents a potential opportunity for antibiotic stewardship. Next steps will evaluate if specific CCC categories predominate in children with complicated pneumonia.