Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics

Session: Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 3: Screening

421 - Replication of a Streamlined Autism Diagnostic Program Embedded in Primary Care: Enhancing Provider and Family Supports via Telemedicine

Friday, May 3, 2024

5:15 PM - 7:15 PM ET

Poster Number: 421

Publication Number: 421.522

Publication Number: 421.522

Jeffrey F. Hine, PhD (he/him/his)

Associate Professor of Pediatrics

Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Nashville, Tennessee, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Long wait times for autism evaluations support the need for increased timeliness of action-steps within primary care. Using embedded specialists and telemedicine to support diagnoses in community settings significantly decreases service delays, reflects high levels of parent/provider satisfaction, and fosters additional opportunities for primary care provider (PCP) training and family support.

Objective: We examined the feasibility of replicating our streamlined diagnostic model within a network of primary care clinics via telemedicine. The objective was to sustain low wait times and an early age of diagnosis across clinics that varied in geography and patient/provider demographics.

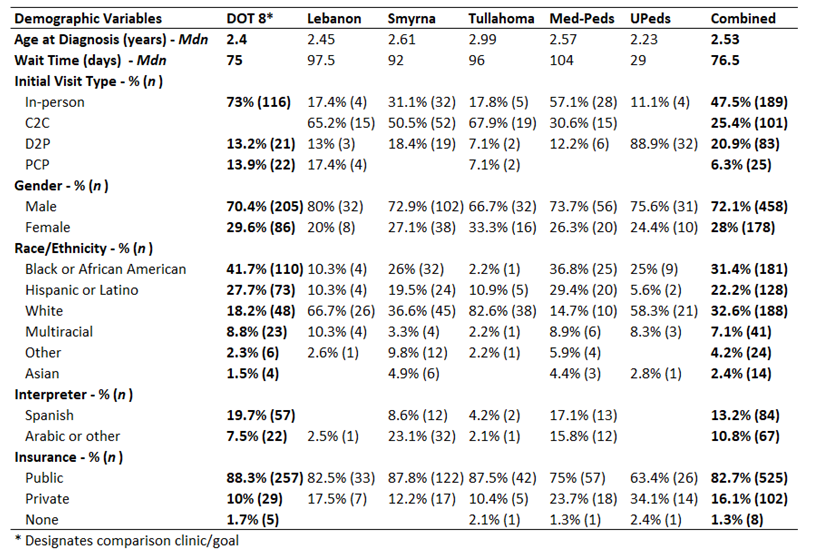

Design/Methods: Children < 48 months were referred from six clinics affiliated with our medical center (Table 1). The “DOT 8” clinic serves as the hub for the model and has successfully implemented autism-specialist embedded services since 2017 (i.e., low wait times, early age of diagnosis, high provider satisfaction; Hine, et al., 2018). Using sustained DOT 8 outcomes as our comparison goal, we studied the feasibility of implementing the model via telemedicine in the satellite clinics, seeing families virtually in their primary care clinic (Clinic-to-Clinic [C2C]) or at home (Direct-to-Patient [D2P]). We extracted data from our electronic health record (EHR) for each child including 1) patient demographics, 2) age at diagnosis, 3) evaluation type (e.g., in-person, C2C, D2P), 4) wait time, and 5) whether the diagnosis was issued by an autism specialist or the child’s PCP.

Results: Data suggest that the telemedicine adaptation of the model was successful, as shown by number of children seen and sustained low wait times and early ages of diagnosis (see Table 1). For all clinics, median wait times were less than 3 months, a significant reduction compared to a 11-month wait time at our tertiary developmental medicine diagnostic clinic.

Conclusion(s): Replicating our embedded diagnostic program with telemedicine supports resulted in sustained outcomes highlighted by shorter wait times and early age of diagnosis. Further, replication clinics served a racially/ethnically/linguistically diverse population and helped minimize common barriers to care (e.g., access to tertiary care, rural locations, lack of autism-specific training for PCPs). Future studies will include in-depth comparison across clinics and the facilitators/barriers of program implementation, including feedback from PCPs/families. We will also discuss current programming related to training PCPs to diagnose and manage autism independently in their own clinics.