Neonatology

Session: Neonatal Follow-up 1

493 - Psychological Transformation Following Trauma: Posttraumatic Growth of Birthing Parents After Preterm Birth

Saturday, May 4, 2024

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM ET

Poster Number: 493

Publication Number: 493.1449

Publication Number: 493.1449

Grace C. Fitzallen, PhD (she/her/hers)

Lecturer

University of Tasmania

South Launceston, Tasmania, Australia

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Preterm birth is a global concern with long-term medical, developmental, and psychological consequences. Posttraumatic stress is well-documented among parents after preterm birth. Nonetheless, posttraumatic growth, defined as adaptive psychological change following a traumatic event that outperforms premorbid functioning, is poorly understood in the context of preterm birth.

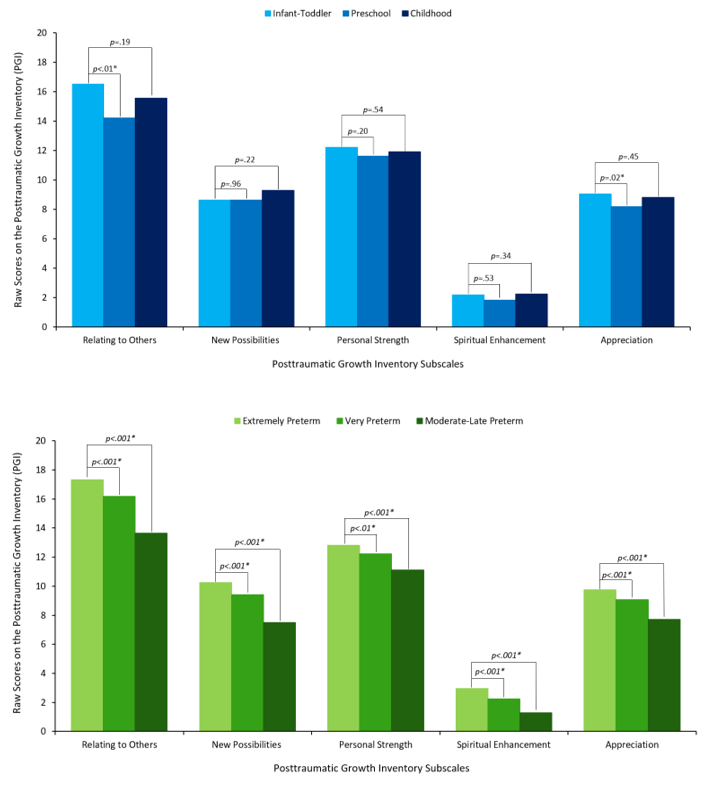

Objective: Describe posttraumatic growth in birthing parents of children born preterm, stratified by child chronological (infant-toddler: 0–2 years; preschool: 3–5 years; childhood: 6–9 years) and gestational (extremely preterm: < 28 weeks; very preterm: 28– < 32 weeks; moderate-late preterm: 32– < 37 weeks) age groups. Furthermore, identifying child and sociodemographic factors associated with parental posttraumatic growth was of particular interest.

Design/Methods: The sample comprised 866 birthing parents of children born preterm (Table 1) stratified into child chronological (infant-toddler: n=308; preschool: n=259; childhood: n=299) and gestational (extremely preterm: n=242; very: n=269; moderate-late: n=355) age groups. Using a cross-sectional study design, self-reports on the standardized Posttraumatic Growth Inventory, which has five subdomains: relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual enhancement, and appreciation, were collected at a single time point.

Results: As shown in Figure 1, parents of infant-toddlers reported significantly higher scores than those of preschool-aged children for relating to others (p=.002) and appreciation (p=.02). Further, parents of children born extremely and very preterm reported significantly greater total posttraumatic growth than moderate-late preterm (p <.001), and on all subscales (p <.001). After accounting for chronological and gestational ages, greater posttraumatic growth was significantly (p <.05) associated with higher neonatal risk, accessing more child therapy services, younger birthing age, ethnic minority, and greater self-reported well-being on the Mental Health Continuum Short Form, accounting for 18% of the variance.

Conclusion(s): Findings demonstrate parental posttraumatic growth after preterm birth differs by child chronological and gestational age, with parents most at risk reporting greater adaptation. While replication using longitudinal study design is recommended, findings highlight the importance of acknowledging positive adaptive experiences following preterm birth. Future research into other psychological mechanisms is suggested to better inform the development of early psychosocial interventions to optimize well-being within the family system.

.png)

.png)