Health Services Research

Session: Health Services Research 3: Access

232 - Access to High-Quality Pediatric Care for Children with Special Health Care Needs who Have Experienced Parental Incarceration

Sunday, May 5, 2024

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM ET

Poster Number: 232

Publication Number: 232.1922

Publication Number: 232.1922

Destiny Tolliver, MD, MHS (she/her/hers)

Assistant Professor

Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Children with special health care needs (CSHCN)—defined as those at risk of chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions requiring health and other services beyond those needed by most children—are overrepresented among the 5 million US children who have had an incarcerated parent. Little is known about CSHCN who experience parental incarceration and their access to well-functioning care systems.

Objective: Estimate the population of CSHCN who have ever experienced parental incarceration and examine relationships between parental incarceration and access to a well-functioning care systems.

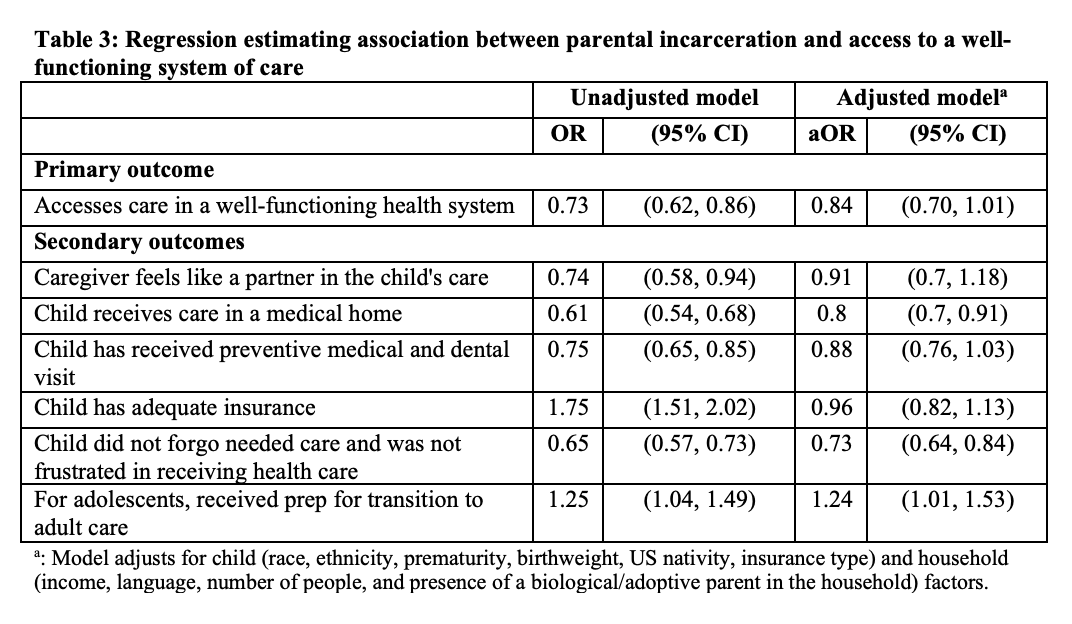

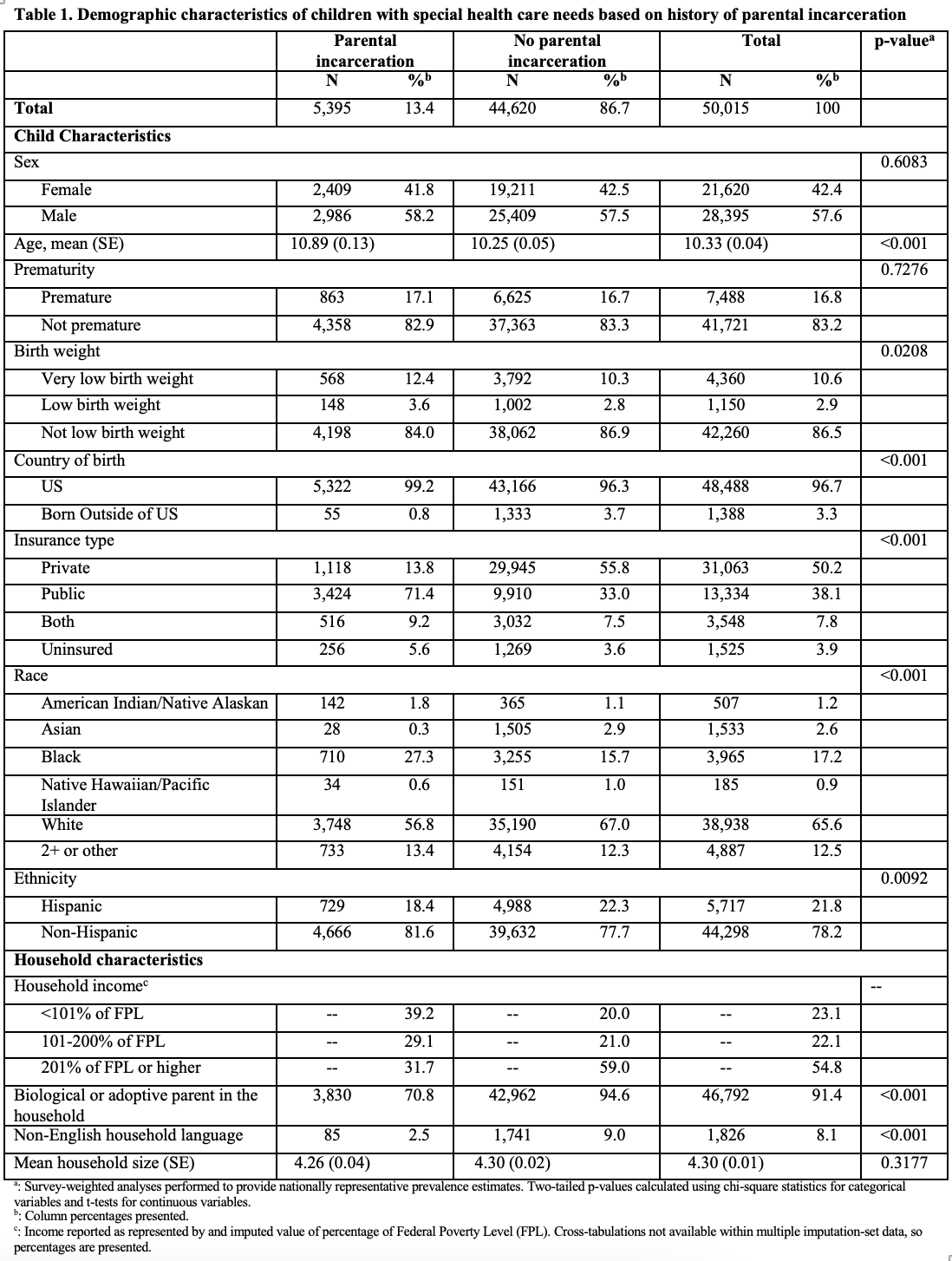

Design/Methods: We performed a cross-sectional analysis of CSHCN ≤17 years old in the National Survey of Children’s Health (2016-21). We used survey weighted percentages and multivariable logistic regression to test associations between parental incarceration and well-functioning care system access. Per the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, we defined access to well-functioning care systems as ≥1 “yes” response and no negative responses to items indicating parents are partners in child’s care; adequate insurance; not forgoing/feeling frustrated accessing care; and receipt of the following: care in a medical home, preventive medical and dental care, and/or adult care transition services (12-17 year olds).

Results: We identified 50,015 CSHCN, 13.4% of whom experienced parental incarceration (Table 1). 14% of CSHCN accessed well-functioning care systems; compared to CSHCN without parental incarceration, a lower percentage of those with parental incarceration accessed well-functioning care systems (11.0% vs 14.4%; Table 2). However, in adjusted regression models, parental incarceration was not associated with access (Table 3). CSHCN with parental incarceration had lower odds of receipt of care in a medical home (aOR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70-0.91) and lower odds of not forgoing or feeling frustrated accessing care (aOR 0.73, 95% CI 0.64-0.84). Adolescent CSHCN with parental incarceration had higher odds of receiving transition services (aOR 1.24, 95% CI 1.01-1.53).

Conclusion(s): While access to well-functioning systems of care did not differ for CSHCN with and without parental incarceration, CSHCN with parental incarceration were less likely to have aspects of well-functioning systems: receipt of care in a medical home and avoidance of the need to forgo care. Given the health and social needs of CSHCN with parental incarceration, better access to well-functioning care systems may advance health outcomes. Positive findings—like higher receipt of transition services—may provide insights to improve access.

.png)